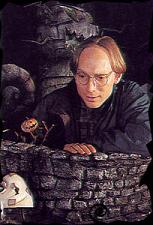

For the release of Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas Collector’s Edition DVD, Disney set up a roundtable discussion between various journalistic outlets and Henry Selick, where questions from the online community could be put to Nightmare‘s director. The film was his first feature, and the prelude to many other successful and critically-acclaimed movies. Indeed, he followed this three-year-plus production with a live-action and animation combo of Roald Dahl’s James and the Giant Peach, which won the top prize at the Annecy International Animation Festival in 1997. He then directed Monkeybone, a fantasy about a cartoonist trapped inside his own creation. Selick, who has continued to chart new territory in animation and fantasy filmmaking, recently created animated sequences for Wes Anderson’s The Life Aquatic With Steve Zissou and is currently directing a digital, stop-motion animated film based on his own adaptation of Neil Gaiman’s Hugo Award-winning, international best-selling children’s book, Coraline.

For the release of Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas Collector’s Edition DVD, Disney set up a roundtable discussion between various journalistic outlets and Henry Selick, where questions from the online community could be put to Nightmare‘s director. The film was his first feature, and the prelude to many other successful and critically-acclaimed movies. Indeed, he followed this three-year-plus production with a live-action and animation combo of Roald Dahl’s James and the Giant Peach, which won the top prize at the Annecy International Animation Festival in 1997. He then directed Monkeybone, a fantasy about a cartoonist trapped inside his own creation. Selick, who has continued to chart new territory in animation and fantasy filmmaking, recently created animated sequences for Wes Anderson’s The Life Aquatic With Steve Zissou and is currently directing a digital, stop-motion animated film based on his own adaptation of Neil Gaiman’s Hugo Award-winning, international best-selling children’s book, Coraline.

After studying at Rutgers University, Syracuse University, and St. Martin’s School of Art in London, Henry Selick eventually enrolled at Cal Arts as part of the first character-animation program along with John Lasseter, John Musker and Brad Bird. He simultaneously studied experimental animation with Jules Engel and made two award-winning student films: Phases, a runner-up in the Student Academy Awards and Tube Tales, also nominated for a Student Academy Award. He later became a trainee at Disney and served as a full animator on The Fox and the Hound, under lead animator Glen Keane. Selick has also written, produced, designed and directed many memorable television spots and commercials.

An impressive figure in the film industry indeed, and Animated News & Views’ Jeremie Noyer was there at Disney’s roundtable to take part in this interview event. The questions and answers are not all Jeremie’s, but all open up the world of Jack Skellington and crew. So, with non-stop e-motion…you’re not dreaming: it’s Christmas before time!

Roundtable Interviewer: You began your career as an inbetweener and animator trainee on The Fox and the Hound. What made you move toward stop-motion animation?

Henry Selick: I’d actually done stop motion prior to working on The Fox and the Hound, including some life size figures for an independent film of mine. While I enjoyed 2D animation while working at Disney, stop-motion had a more visceral charge to it and was therefore where I was always going to end up.

RI: What do you mean by “visceral charge”?

HS: I love all sorts of animation, probably the most beautiful would be the traditional hand drawn animation that Disney is known for. Stop-motion has a certain “grittiness” and is filled with imperfections, and yet their is an undeniable truth, that what you see really exits, even it if is posed by hand, 24 times a second. This truth is what I find most attractive about stop-motion animation.

RI: What stop-motion film got you excited as a kid and inspired your career path?

HS: The early Harryhausen, Jason and the Argonauts in particular. I also love Seventh Voyage [Of Sinbad], the best cyclops that will ever be done. There was just this wonderful sense that Harryhausen’s monsters were real, despite the sort of lurching quality they had, they had an undeniable reality to them.

RI: How did you originally come on board to the Nightmare Before Christmas project?

HS: I was working with Tim at Disney in the early 1980s when he first conceived the poem and idea of Jack Skellingon taking over Christmas. Sculptor Rick Heinrichs took the original characters designed by Tim: Jack, Zero and Sandy Claws and created beautiful maquettes that showed what they’d be like as stop motion characters. It was originally pitched to Disney as a TV special but was rejected. I had moved to Northern California where I worked as storyboard artist and a stop motion filmmaker with short flims, TV commercials and MTV. While Tim went on to achieve great success in live action, I got a call from Rick and he said there was something important we must talk about in person. He flew to San Francisco and said Tim is making Nightmare Before Christmas and wants you to direct it. I met with Tim and Danny Elfman and my small crew that I had been working with immediately became supervisors on a feature film.

RI: Do you see any connection between Nightmare and Vincent, the short present in the bonus features of the DVD?

HS: Vincent was Tim’s first stop-motion film that he made with Rick Heinrichs. It had a striking look, bold design and was basically part of Tim’s growth as an artist, which influence the look of Nightmare Before Christmas.

RI: Was there resistance at first to do Nightmare as stop-motion instead of cel animation?

HS: There was resistance to doing it all at first. When Tim first pitched it to Disney in the early 1980s there was resistance to the project in any medium. But ten years later when the film was made there was never an issue about it being stop-motion. It was simply a case of that is how Tim conceived it.

HS: There was resistance to doing it all at first. When Tim first pitched it to Disney in the early 1980s there was resistance to the project in any medium. But ten years later when the film was made there was never an issue about it being stop-motion. It was simply a case of that is how Tim conceived it.

RI: How was your crew?

HS: Virtually all animation is labor intensive, since it was what I do it did not seem any harder than others. The small army topped out at under 200 people. Because the range of talents and abilities, there was always something amazing and wonderful to see virtually every day, so that the long journey of production was re-inspired regularly. We used Disney’s fledgling effects unit in Burbank and they created the very simple snow that falls at the end of the film. Other than that it was all pretty much done by hand in house.

RI: Joe Cockley once said that you and Tim Burton took a lot of your people from his Gumby crew. Did you?

HS: There was a Gumby revival by Art Clokey in the 80s and a new TV series that followed, which attracted a lot of young stop-motion animators to California. Many of the animators for Nightmare Before Christmas came from that group. But the Gumby project had been over for almost three years so we did not ‘take’ anyone.

RI: How was your working relationship with Tim Burton?

HS: Working with Tim was great, he came up with a brilliant idea, designed the main characters, fleshed out the story, got Danny Elfman to write a bunch of great songs. He got the project on its feet and then stood back and watched us fly with it. Tim, who made two live-action features in L.A. while we were in San Francisco making Nightmare, was kept in the loop throughout the process, reviewing storyboards and animation. When we completed the film Tim came in with his editor Chris to pace up the film and make a particular story adjust to make Lock, Shock, and Barrel just a touch nicer.

RI: Do you think it benefited you and your team being in that San Francisco warehouse creating Nightmare instead of in Burbank where you might have people standing over your shoulder and freaking out at what you were creating? Or were you given autonomy because of Tim Burton’s track record at the time?

HS: Being in San Francisco helped protect the film from “lookieloos”.

RI: How early in the process was Oogie Boogie developed. After seeing the original poem, Jack certainly is borderline on the evil side…so I’m assuming having Oogie was there to expand things, but to also take the edge off of Jack.

HS: Oogie started out as the size of a pillowcase and not that scary or evil or important, but as the story developed I felt the need to grow him in both his scale and his role. Ultimately Danny Eflman’s Oogie Boogie song is what truly defined his character as THE villain and Jack’s role was fully defined as a misguided hero.

RI: How was it to deal with that character?

HS: He was a huge puppet, very difficult to muscle around it was almost as if he was trying to push back while you were animating him.

RI: Was there a character created for Nightmare that you loved, that never made it past the conceptual stage?

HS: No, we were desperate to flesh out the town, after you go through the mummy and vampires etc it gets slim. We used everything we came up with.

RI: You once explained that The Man with the Tear Away Face had to be tempered because it was too scary originally — were there other sequences that had to be altered during production because they became more intense?

HS: No, that is the only studio note that was actually implemented.

RI: Who was your personal favorite character in Nightmare?

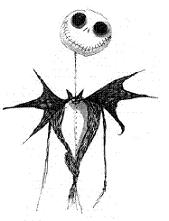

HS: The one I’m closest to is Jack Skellington, because as a director you often have to act out various characters for your animators, since I resemble Jack Skellington more than the other characters , I think more of my gestures got into Jack.

RI: What was the most intricate scene (stop-motion wise) to complete?

HS: While virtually every bit of the stop motion animation was challenging, there were several particularly difficult scenes to pull off , one began where Jack is shot out of the sky with his Skellington Reindeer flying over head and being shot down, and lands in the arms of the angel statue in a graveyard and goes on to sing a song there while the camera continuously circles him. The opening song of the film This is Halloween was monstrously challenging as it introduced all the Halloween Town monsters to the audience.

RI: How did you get such a fluidity in the animation? Did you use any complementary technology in addition to traditional stop-motion/hand animation?

HS: We don’t think we actually achieved a very fluid motion, so thanks for the compliment. It was basically made the same way the original King Kong was made or any of Ray Harryhausen’s creatures.

RI: What makes stop-motion worth all the effort in a CGI-obsessed industry?

HS: People are always going to be drawn to something that is shaped by the human hand in an undeniable way. So that while Ray Harryhausen was going for perfectly smooth animation, it is the unavoidable imperfections in his work that give it soul and make it memorable.

RI: How is the directing process on a stop-motion film different from directing live-action or even regular animation?

HS: Directing stop motion animation is actually a sort of combination of directing live action and ‘regular’ animation. We have real sets, real lights, real cameras. There is a costume department, a hair department and our puppets are the actors. Like regular animation it is a divide and conquer. It is all divided up into manageable pieces, edited in storyboards before the movie is made and then shot a frame a time like traditional animation.

RI: Do you think the Best Animated Feature Oscar category does more good or harm for the medium?

HS: More good!

RI: What was the biggest lesson you carried away from the Nightmare Before Christmas experience?

HS: When possible always work with geniuses like Tim Burton, who are not only creatively inspiring but in his case, also have the clout to protect the film from the studio system.

RI: Has it surprised you how much Nightmare has been absorbed into the pop culture stratosphere — goth kids at Hot Topic wearing Jack belts and arm bands and the like?

HS: At this point, 15 years later after the original release, I’ve grown used to seeing Jack and Sally turn up all over the place. But this did not happen right away it has taken years for our initial cult audience to grow into a pop culture phenomenon. Just this past Halloween, we had some girls show up at the house in N B Christmas costumes and my wife and I pointed out one of the original Jack Skellington and the Skellington Reindeer which was in our office, it blew their minds and they screamed with joy, taking their handfuls of candy and went away just full of life.

RI: Do you find it ironic that Nightmare has become a Disney property, when it was originally released as a Touchstone picture? When did you start seeing the shift with Disney embracing the film?

HS: Yes. Nightmare was just too different from what Disney was having success with. Although I don’t think Walt Disney himself would have had a problem with it being labeled a Disney film. Just check out some of the sequences from Fantasia, The Legend of Sleepy Hollow, Ward Kimball’s goons and monsters in Sleeping Beauty, etc, and you’ll see Nightmare and its characters were carrying on in the same tradition. While it took sometime, about seven years ago when The Haunted Mansion at Disneyland was transformed into a Nightmare extravaganza, we then felt we were truly loved by the Disney label.

RI: Have you ever considered returning to the world of Nightmare Before Christmas?

HS: There has been discussions over the years about a possible sequel. When those discussions came up about seven years ago it was unsettling that it was suggested this time it would have to be done in CG. I’m glad that did not happen. But as far as coming up ideas for a sequel, you have to admit there are a lot of other great holidays for Jack Skellington to take over.

RI: What is the next step in stop-motion technology? We’ve read about the new stereoscopic dual digital camera rig you’re using on Coraline. How will the end result be different from Nightmare Before Christmas?

HS: Shooting stereoscopically just gives you more of what is there, just a little more sense of the reality of this medium, it does not live in the computer nor is it a series of drawings, it’s an actual real set and puppets.

RI: Do you intend to pursue working in other mediums of animation or will stop-motion remain your field?

HS: I was a 2D animator at Disney and I’ve done some CG work, but I’d prefer to keep with stop-motion animation.

RI: People who have directed 3D/CGI tell me that stop-motion people have certain advantages adapting to CGI over more traditional techniques. Do you find that to be the case? If so or not, why?

HS: It is simply the fact that what were shooting really exits. So you get immediate feedback and can make adjustments accordingly.

RI: Would you ever do a short film for NBC writer Caroline Thompson’s new company, Small and Creepy?

HS: Sure I’d love to do a short film for Caroline Thompson’s company. She did a great job shaping the film’s story from Danny’s songs.

RI: How far along is Coraline?

HS: We will complete animation on Coraline in about 6 weeks and plan a February release for 09.

RI: What was it about Coraline that truly appealed to you?

HS: It’s a dark perfect modern fairytale that concerns itself with a primal thought every child considers; I wish I had other parents. That, and the button eyes.

RI: How direct of a translation is Coraline from Neil Gaiman’s book?

HS: The movie version of Coraline is very faithful to the tone and the spirit of the book. In the translation from book to film there are adjustments to story and character that have to be made. The main thing I always felt was I could not disappoint the readers of the book, and though some details have been changed and as well as the order of the sequences, I feel we will be successful.

RI: How will your experience working on Nightmare influence your upcoming project, Coraline? How will the aesthetic and visual style compare to Coraline?

HS: You build on what you know, so there is no doubt that some similarities between the two projects. I also have many of the original Nightmare team members working on Coraline. We’ve all grown and the visual aesthetic is ultimately a very different one. You’ll see great animation like Nightmare, like a cousin of Nightmare. More like a second cousin. The last thing I’d want to do would be to try to rip off a classic film I directed.

RI: How would you compare adapting Neil Gaiman in Coraline with adapting Tim Burton’s designs on Nightmare?

HS: I think that both Tim and Neil are extremely imaginative and real creators. In Tim’s case he is a visual artist so the look of the film came from his sensibilities. Neil is not a visual artist, so I created the visual look of Coraline, but as far as sensibilities, I think there is a little more whimsy in Tim’s work, a little more sweet with the sours, comfort with the scary, but I’d probably exclude Sweeney Todd. Neil goes a little more darker, primal like a Grimms’ fairytale.

RI: What major changes have occurred in this kind of filmmaking in the time between Nightmare and Coraline?

HS: Mainly it is the ability to capture images in a computer while you shoot. When we did Nightmare we could capture 2 images total. Now you can shoot the whole scene and play it back while you animate. This assists the animator but actually slows down the process because they keep checking it every time they shoot a new frame. Computers have slowed down what is already a time consuming process!

RI: Does a film like Nightmare naturally look amazing in high def or does the translation and remastering take a lot of work?

HS: The fact is the film was originally shot in 35mm film, each image is pristine with no blur, so the source material is already high def , more so than a standard film, so the mastering is less of a challenge.

RI: The DVD already makes the animation look so clear. What new details will we notice in Blu-ray?

HS: Some of the details that may become apparent in Blu-ray are that we tried to add texture to all the characters and backgrounds as if they were an engraving, for example you’ll see that Jack’s stripes on his suit are hand drawn, and the hills behind also have hand made textures built into them. Additional details would be things like the leaves that Sally is stuffed with, the bugs inside Oogie Boogie. Look into the shadow areas, there are hidden details there that have never shown up on previous DVDs but will show up on the Blu-ray.

RI: How many of the original puppets do you have in your house?

HS: The main one I have is Jack Skellington as Santa with his Skeleton Reindeer in his sled led by Zero. It is prominently displayed in my office where occasional trick or treaters get let in IF they are wearing Nightmare Before Christmas attire!

is available to buy now from Amazon.com

With all our gratitude to Henry Selick and Mac McLean!