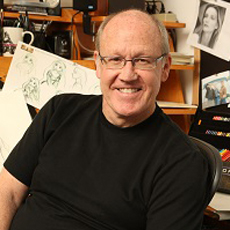

He’s presently one of Disney’s top character designers and animators. In a way, he’s the daddy of Ariel, Beast, Aladdin, Pocahontas, Tarzan, John Silver and Rapunzel, among others. He’s an artist and a mentor.

He’s Glen Keane.

Last week, Animated Views took part in an amazing roundtable with Glen as he gave us the most intriguing lessons of animation, reminiscing the stories behind the creation of one of his most successful characters, and certainly one of the deepest Disney characters ever – the Beast from the Studio’s celebrated Oscar-nominated feature Beauty And The Beast, now available in a new Diamond Edition DVD and Blu-ray.

Roundtable Interviewer: Beauty and the Beast is one of the most ancient stories, going back certainly to Cupid and Psyche and Oedipus. And what makes this unique, I think – and Glen, you probably would agree – is that every culture can relate to this because every culture has some version of this fairy tale.

Roundtable Interviewer: Beauty and the Beast is one of the most ancient stories, going back certainly to Cupid and Psyche and Oedipus. And what makes this unique, I think – and Glen, you probably would agree – is that every culture can relate to this because every culture has some version of this fairy tale.

Glen Keane: Yes. Well, it’s a story that really touches the heart of everybody who sees it. Though when we were doing research on this, it’s difficult to find the key that’s going to unlock the fairy tale for a Disney animated movie. It’s one thing to have a fairy tale that you can read to a child before they go to bed, but it’s another to have a story that’s going to carry for an hour and a half and will have all of the emotional, dramatic impact. And in this story, the struggle we had was it really takes place at a dinner table, and every night Beast says – asks Belle if she will marry him, and that’s just not quite thick enough for an animated movie.

RI: I guess Walt Disney himself did do some early explorations on the story.

GK: Yes, and that was – I think what I just said – was one of the reasons why he put it down, that there were other fairy tales that were much more accessible and that you could build the story out of it in an easier way. Some of the stories that were the later fairy tales are the harder nuts to crack of these big, iconic, classic fairy tales that the world knows.

Joe Grant, who was head of story on Snow White, he was still alive at the studio at the time as – and he had done some work on our new Beauty and the Beast, but he had also done some work on the old version, the original one that he and Walt were trying to crack. And he just said, “Oh, it was just frustrating. We just couldn’t do it.” We put a lot of things on the shelf and figured that, well, someday the time is going to come, and we’ll pick it up again. And he just happened to be living long enough where he was there to pick it up again.

RI: And so, that began in 1987, correct?

GK: Yes.

RI: And with that, a pretty extraordinary team of animators was put together for this film.

GK: Yes. There was Andreas Deja, who did Gaston, and then Dave Pruiksma did Mrs. Potts, and Will Finn that animated Cogsworth, and Nick Ranieri that animated Lumiere. They were both just like Cogsworth and Lumiere throughout the whole movie, at each other’s throats.

RI: What about your research trip to France?

GK: Yes. Well, for me, if you’re going to work on a Disney movie, it’s not just about doing drawings of interesting characters – it really takes place. There’s a truth to the environment. And I’d never been to Europe before. I felt like I personally really needed to go visit the place where this fairy tale was written, so we – as well as each of the artists that were there.

So we went over to the Loire Valley in France where the River Loire runs along. And as you probably all know, the different chateaus are built within a day’s ride for the king to go from one chateau to the next to the next. And so, we would drive and hit several of those in a day because we didn’t have to go by horse – we had cars – and we would visit these places.

And there was one chateau that just stood out as stunning. It was the one of Chambord, built by François de Pontbriant. And he designed this castle that just had this imposing power and strength to it. And the truth of that place adds credibility to your drawing in a funny kind of a way.

I guess, you know, just to explain to you a little bit about how I think, and when I was a kid, I didn’t do drawings to do a drawing of something. I did a drawing so I could enter into an imaginary world. My paper was like a magic mirror that I could do a drawing, and you just step right through it and suddenly you’re living in the time of the dinosaurs, or you’re living somewhere and you’re experiencing it. And that with that castle, that was really important as a place where I could step into it.

RI: How did you find the right design for the Beast?

GK: I found this buffalo head at a taxidermy shop not too far from where our studio was in Glendale, and so I bought it and brought it into my office and just had it on the wall as a reminder of just how big this character is, a huge animal like that.

I also got interested in 19th illustration. There was a tendency there to just take the head of a wild animal and stick it on a man’s body, like – well, up on the one with Walter Crane, you can see it’s basically a man’s body, but at the very bottom he’s still got his hooves of a wild boar, but the head is just like a regular wild boar. The same one with, let’s see, Edmond Dulac and Warwick Goble.

The wild boar is a pretty interesting version of the character. Arthur Rackham’s version is an interesting one because he kind of looks sort of alien, in a way. And so, I was looking at all of these characters and trying to find something that was going to serve for inspiration for me.

And the problem that I kept coming up with was that – well, there’s two things. One is the – you take it very seriously when you’re going to design a character for a Disney animated movie. You know that that character is going to become the definitive version of that character for all time.

So you don’t just jump in and just draw something that pops out of your head. There has to be a sense of rightness, of like, yes, almost like you discovered what was already existing before you even started to draw it. I’ve always had this feeling that, on any character that I’ve animated, that the character existed before I started to draw it, and it was – it’s a little bit like Michelangelo sculpting in stone and freeing the figure that’s within.

You have that same sense of drawing on a piece of paper that’s blank and empty, but there is a character in there. And it has to touch and connect with you and the audience. And to me, it was important that this character not feel like he was an alien, like he was invented for Star Wars or something. This one of Arthur Rackham feels a little bit like that to me. He’s a weird creature.

For me, it was equally important that the credibility of this character be based on true – you know, to me, true animals. There were various different designs. These were some of Chris Andrews’ designs, and they were very whimsical. Some of Andreas’s designs, too, which I thought were pretty cool and interesting, but nothing was really jumping out and speaking to me. We had quite a variety, actually.

There was one – at the zoo – there was a mandrill named Boris that I would pass by and I would do drawings. This is one of the drawings I did there in London at the time, thinking of the Beast as a mandrill-like character. But ultimately, the Beast came down to a variety of real animals for me. There’s different kinds of feet and, you know, claws, exploration of a wide variety of characters that we explored.

You start looking in magazines or – for animals – and there’s this power of the gorilla. So I had the gorilla up there, or the lions, you know, and I would draw them. And I had these wild boars. I actually had the head of a wild boar, as well, on my office. There was that buffalo head, the big sadness, the heaviness of the buffalo head.

And then, there was these wolf legs. And as I started you, know, walk past – back and forth past the zoo, I guess the wolf was the first clue to me that all the drawings that I had been seeing of the past illustrators’ works of the Beast always had him standing on kind of human legs. It might change just his toes or whatever, but I started thinking of The Beast as a wolf leg because it would really always remind you of his animal-ness on the bottom part as well as the top part.

So that was the first thing, and then also go give him a tail that would switch back and forth. And, it’s like, if you have a dog, you know that you can tell if your dog’s happy. You’re sad. You just look at the tail. And now, that gave another whole aspect for the Beast. His body – I really like the power and the massiveness of that bear – and started drawing him on all fours, because that got me away from this just guy in a beast head, the Halloween mask or something. I really wanted him to be animal.

And so, the more I could explore and start to draw that character…actually, there was one day I had an animator on our team, Bruce Johnson, who was going to be one of the animators of the Beast, came in. And Bruce said, “So what’s the Beast going to look like?” This is after, like, six months of drawing and searching, and I – all of these photos on my wall – I said, “I’m not sure, Bruce. I don’t know.” I started to draw. I said, “I like the massiveness of this buffalo head”, and I sketched out the weight, “and of this buffalo head”, I said, “But the brow of the gorilla,” and I drew the brow there. “But then the muzzle of this wild boar,” and then the mane of a lion but the body of a bear, and then the legs of this wolf.

As I did it, it just all came together. And like I was telling you before, there’s this moment where you recognize the character. And I looked at it, and I said, “That’s him. That’s what he looks like, like that, Bruce. That’s what – that’s the Beast.”

And it was just one of these wonderful little gifts from Heaven that happened at that moment, you know? I wish I could take more credit for it. It just happened. And the thing is that he has to be appealing. See, that appeal was the thing that I kept hearing all the time from the masters at Disney that taught me, Frank Thomas, Ollie Johnston, Eric Larson would say, “Your animation has to have sincerity and appeal.”

RI: Precisely – how did you manage that aspect?

GK: Well, at the beginning, I really needed to learn the lesson, I think, you know, that beauty is only skin deep, because I did not believe – that the audience would believe – that Belle would fall in love with this beast.

As I drew him, I knew that I had to communicate the wild animal nature to him. That was the easy part. I had animated a bear in the Fox and the Hound, and the ferocious wildness of this grizzly bear. I just drew on that for me in animating the Beast at the very beginning.

It was the middle zone where he starts to turn – that was, as I had said, seeing the childlike. It went from wild animal to selfish human nature. And then, at the end, the hardest scene for me to animate in the whole movie, though, was the moment where Beast lets Belle go back to go back home. He’s standing there looking at the rose under the glass, and he knows that he will die, but he doesn’t tell Belle that. He lets her go back to see her father.

And Cogsworth comes in and says, “You let her go. Why’d you do that?” And he says, “I love her.” And it was trying to animate that line, nothing I did felt like it could communicate that arc, that change, that truth that went on in him. So the times like that, you just – you just trust that the music, the story that’s led up to it is going to carry it through, because nothing that you can draw feels adequate.

Well, one of the really fun aspects of the Beast was this – the wild animal side next to this girl. And basically, though, we had to break that down into what does that mean in human nature. What is a wild animal like in us in human nature? Well, it’s selfish. It’s very immature.

You know, our little granddaughter, I’m watching her deal with problems by her petulance and, you know, by saying no, and that basically was the Beast’s problem. That’s why all of this came, because he hadn’t learned to love. And so it was fun watching Belle just wrestle a beast in his nature, just wrestling that down. And these images from the film show this wild animal side and her standing there next to him.

The biggest challenge we had was, in my mind, how is the audience ever going to believe that Belle could fall in love, to earn this moment where they dance together? Because at one point in the film, after Belle heals his hand, and we went pretty quickly to this moment here. And that was after the Beast saves here, and we felt like that should be enough.

But something was missing. You didn’t really feel like you earned this dance. And at that point, Howard Ashman, who had really created the tent poles for our story, realized that we were missing an extremely important tent pole, and he wrote a song called Something There, this moment where Beast gives Belle the library.

And it was so subtle and gentle of a thing that it had escaped us, that true love isn’t just like Beast going and battling the wolves seemed like, “OK, well that’s the dramatic indication of his love for her.” But it was him noticing how this girl loved to read and that he presents her with the library. And it was the little things, like a flower growing, that’s what that song was about. And as soon as that was written, we knew the movie was going to work. And that happened pretty late, that last year, actually, in production. So we didn’t know that it was going to work until that point.

And then it earned the right to have this wonderful sequence with the Beast dancing with Belle. These are actually drawings from James Baxter of the Beast with Belle. James and I actually got out there, and we danced together. We had a dance coach helping us learn the steps, and when it came down to it, he did the animation on this. I drew over top of it.

RI: Another magical moment is the transformation of the Beast into a human being.

GK: It was the last scene that I had to do on the film, kind of the one that I’d been waiting for through the whole movie, to animate this transformation. Well, we finally got down to the end, and there was no time left. I had one week left to animate this whole wonderful sequence that I felt like I was born to do, but now there was no time. And Don Hahn came into my office, and I expressed to him my frustration.

I said, “Don, I can’t do this in one week.” And he could see, like, the panic in my eyes, and he said, “Glen, look, just take whatever time you need. I will push back the deadline in whatever way we can to give you the time to do this.”

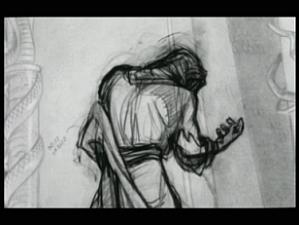

So I took a sigh of relief and left work and drove down to the Norton Simon Museum, which is where this sculpture is, the Burghers of Calais, by Rodin. And as I walked around, I started doing drawings of these figures, and particularly it was the back, the way that he sculpted the form of the back. There was such power in that.

And you don’t know how you’re going to unlock a sequence, but to me, it was the back of the Beast that I wanted to see transformed, but to do it in space like I was walking around the sculpture there, doing these drawings of Rodin’s. And as I did that, I realized this is what I want to see happen. I want to rotate the Beast in the air. I want to see, like, the back changing, and it will move up and slowly see his arms and his hands and his feet, and finally his head. And that’s what inspired this sequence here.

To me, animation, I think of it as sculptural drawing. I shade all of my drawings. Animators say to me, “Why are you shading your drawings? No one’s going to see the shading.” It’s like, you could get that done so much quicker if you didn’t do the shading, but I would never do the drawing like this, so I didn’t do the shading. It’s all about light and form and space.

As the Beast turns, we see his head up in the shadow, come out of the shadow. Now I’ve staged it and set it up so that there’s something delicate can happen, and it was the wind. To me, the wind is like the spirit of God that does this transformation in our lives. I’d always related to the Beast very much like in my own life spiritually, a transformation, that my faith in God and feeling like there was a lot of things in my own life that I could look and say that I’ve matured from.

And so, this is this moment where this spirit, this wind starts to blow on the Beast’s face. I don’t know if how far we go with that, and that all goes by amazingly fast, ridiculously fast, and you look at it and you go, “So what’s the big deal about all this?” Well, it’s all – everything that happened before that – it’s all the setup that you spent an hour and a half building for this moment where you could really satisfy the audience’s thirst to see this transformation.

And it was – you were setting it up for actually when Belle looks into his eyes. That’s where you wanted to take the time. I mean, you could take, I don’t know, a half-hour on any one of these sequences and just watch that transformation, but we really wanted to play the time for Belle to be looking into his eyes.

RI: What memories do you have of Roy Edward Disney?

GK: Well, Roy has always been like the godfather of animation for us from early, early on, and so he was very involved with us, coming in often to the studio, seeing how things were going with us. He gave me – like, he’d buy some pencils, I remember one time, that he was thinking of me. He was at some store, and they had these gorgeous pencils, and he wanted me to have them so that I could be drawing with them.

He wasn’t going to be animating, but he wanted to participate with that. He was constantly encouraging, sending little, I don’t know, clips of things that he would read, pieces of music that would inspire him. He was a very sensitive soul. And we felt very protected knowing that we have somebody like that whose name is on the head of the building, you know, that cared like that.

RI: What do you think of the Broadway version of the Beast?

GK: Before we did the play, I sat down with the designers, and we talked about all the research and development that went into that character. I was really trying to stress some of the essentials, like the scale and the size of the Beast, how important that was, the animal nature, the way that he would move around. And their limitations on stage are entirely – you’re limited. You can’t just do anything that you could draw.

But there were some things that I was just amazed at how clever their solutions were, like the transformation, that the Beast actually – it’s his clothes – his Beast costume is just sucked off by a vacuum, and there’s this transformation that happens with the cloud in front of your eyes, and you don’t see it. It was a magic trick for them. They actually had to physically do what we could just fake with our drawings. I was impressed.

RI: Thank you so much for that lesson of animation, that is at the same time a lesson of life!

GK: The whole point, I think, is behind all of this is to give you a sense of the work that goes into animating something that is all behind the scenes. It’s described in a term that I learned from the Renaissance by a man that was trying to describe the work of Raphael. And he said, “It’s Sprezzatura.” And sprezzatura means art that hides its art.

That’s what animation is. It’s an art form that’s hiding all of this that we’re showing you right now, because really, in the final color, you’re just following along, believing the character is real.

Our gratitude goes to Glen Keane, Dre Birskovich and Mindy Johnson