The 1940s ushered in an era of musical experimentation and innovation at the Walt Disney Studios. Artists from all over the world flocked to California to be part of the magic, and their groundbreaking styles influenced such classics as Dumbo and Bambi, and shaped the masterpieces that followed, including Alice In Wonderland and Peter Pan.

The 1940s ushered in an era of musical experimentation and innovation at the Walt Disney Studios. Artists from all over the world flocked to California to be part of the magic, and their groundbreaking styles influenced such classics as Dumbo and Bambi, and shaped the masterpieces that followed, including Alice In Wonderland and Peter Pan.

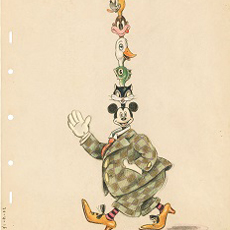

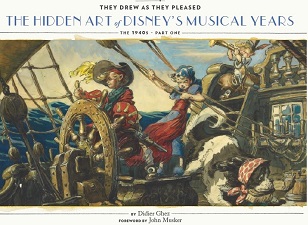

They Drew As They Pleased: The Hidden Art Of Disney’s Musical Years, the second volume in the critically acclaimed and groundbreaking series by Didier Ghez, examines this particular period as never before. For this volume, Ghez has unearthed hundreds of enchanting images, from early sketches to polished concepts for iconic features, by five exceptional artists: Walt Scott, Kay Nielsen, Sylvia Holland, Retta Scott and David Hall, who shaped the style of the Studio’s animation during this period of unbridled creativity. This book is undoubtedly a gem in the field of the history of the Disney artists, but also Disney musical history, unveiling never before heard information about how seriously music was approached during that time.

Didier kindly accepted to talk with us about those “musical” years and the fascinating discoveries he made.

AnimatedViews: Your book examines art during Disney’s “musical” years. Please, would you explain the musical specificity of that period?

Didier Ghez: The volume of They Drew As They Pleased dealing with the 1940s was originally supposed to be one single book. Very early in the process, though, I realized that the late 1930s and the 1940s was such an amazingly creative era at the Disney Studio that I needed to split the volume in two. There were at least eleven key artists to discuss! Fortunately, Chronicle Books was receptive to the idea. Of course, this also meant that I had to organize those artists by theme. I knew that Volume 3 (The Hidden Art Of Disney’s Late Golden Age) would deal with the artists who were part of Disney’s Character Model Department. The question became: what is the link between the five artists I planned to feature in Volume 2? If you look at the late 1930s and at the 1940s, you realize that two of the historical themes that dominate are the 1941 Disney strike and World War II. That was pretty obvious, but it did not really help me. If you look at the creative history of the Studio, though, you also notice that the two dominant themes are the creation of the short-lived Character Model Department and its influence throughout the ‘40s, and on the other hand the musical projects that the Studio was working on in those years, from Fantasia to the package features. In fact, when you look at the 1943 internal lists of projects that the Studio drafted, you can see those projects organized as “shorts,” “features” and “musical projects.” So Volume 2 naturally became The Hidden Art Of Disney’s Musical Years. It features Walt Scott, Kay Nielsen, Sylvia Holland, and Retta Scott, four artists whose careers were heavily tied to those musical projects. The fifth artist who deserves a chapter in the book is the ground-breaking David Hall. David was not involved with the musical projects, nor was he part of the Character Model Department, but I had to include him somewhere and I have a feeling you will love to discover his artwork in this book.

AV: How did you find about Heinrich Tandler and his extraordinary musical library?

DG: When I started researching the art and life of artist Sylvia Holland (one of the most versatile Disney artists, and a woman who almost became the first female director at the Studio), my good friend and fellow Disney researcher Joe Campana and I stumbled upon a true treasure trove of written documents that had been preserved for more than 70 years by her family. This was one of the most exciting finds ever. The collection took no less than six months to scan. Among the papers that had been preserved were several that were linked to a department of the Studio that I had no idea existed at the time: the Music Library. We all knew about the book library (I describe the origins of that department in the first volume of the series) but the music library was a mystery to me. I wanted to understand a lot more about its genesis, and by digging into some rare documents in the Sylvia Holland collection, at the Walt Disney Archives and in other private collections, I stumbled upon the names of Heinrich Tandler, Marcia Lees and a few others. By focusing on the dates at which they were hired, I also realized that Walt, as was often the case, never focused solely on generating creative ideas. He also followed up with new structures within the Studio that would give him the means to reach those creative goals. Case in point: Walt hires Heinrich Tandler, who becomes the head of the Music Library the same month as he acquires the rights to Paul Dukas’ The Sorcerer’s Apprentice! This is not a coincidence, of course.

AV: In what way did that library influence the films to be produced at that time?

DG: The Music Library soon included hundreds of recordings, ranging from classical music to circus music, congas, musicals, music of the world, Negro spirituals, tangos, and even nursery rhymes—everything from Benny Goodman to Richard Wagner and more. Like the book library, it was used by the Disney artists as a constant source of inspiration.

AV: You mention the visit of Sergei Prokofiev at the Studio in February 1938. Could you tell us about the circumstances and motivations of such a surprising move?

DG: Here is what we know and what I write in the book about this. Remember that by February 1938 Disney was hard at work on The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, a project that was already morphing into what became Fantasia. “[In February 1938, Walt Disney] and Studio composer Leigh Harline met with Russian composer Sergei Prokofiev and his lawyer, Randolph Polk, and listened to Prokofiev play the piano score of Peter And The Wolf. During the visit, Polk recalled two years later, ‘Prokofiev explained that he had written this composition with Mr. Disney in mind, and that it was his one great desire to have Mr. Disney acquire this work for use in one of his feature pictures.’ Though the music was not used in ‘The Concert Feature,’ in 1946 Peter and the Wolf was included in Make Mine Music.”

AV: Can you tell me about Ed Plumb, who is to me rather underestimated, and what you learned about him while contacting his family?

DG: Here is what I wrote in the book about Ed Plumb: “Ed had been hired in March of 1937 on the advice of the head of Disney’s Story Research Department, John Rose, who had studied with him at Dartmouth. ‘Ed Plumb was really the musical genius behind Fantasia,’ explained Rose. ‘[He] was capable of taking the original Mussorgsky sketch for Night On Bald Mountain. . . and to go ahead and orchestrate it the way he felt Mussorgsky would have done it had he lived to do it himself. . . . Without Plumb, I doubt that we would have gotten into Fantasia.’ Even more so than conductor Leopold Stokowski, Ed Plumb became the soul of the Fantasia project and its unsung hero.”

AV: It is amazing that Disney envisioned for a moment to use Fantasound also for Bambi. Can you tell me more about that project?

DG: We do not have a lot more details about this, but before the release of Fantasia, Roy mentions the idea very seriously in a memo to Walt.

AV: You uncovered extraordinary pieces for your book that were “hidden”. Can you share some of your most exciting quests?

DG: We could write a whole book about the research process. But here is one of the most exciting examples. When I started researching the life and career of Disney’s first female animator, Retta Scott, who also happened to be a talented member of the Story Department, I contacted Retta’s sons. One of them did not have any material about his mother. The other told me: “I have very little, just a few autobiographical notes.” I was excited about those, of course, since autobiographical notes, like correspondence and diaries, are a real time machine for historians. I told him so and he sent me those notes. By reading them, I realized that Retta, after having left the Disney Studio in 1946, had gone back to the animation field more than 30 years later, in the 1980s. This was exciting since it meant that there must be a few people still alive who would have worked with her at the time. I tracked some of those artists down and interviewed them. One of them mentioned something that really excited me: while Retta was working with that artist in the 1980s, she had brought the mock-up of a kid’s book titled B-1st which she had created in 1941 with fellow Disney artist Woolie Reitherman. I immediately emailed Retta’s son, and he mentioned that he owned the mock-up!! If he had preserved that mock-up, what else was there to re-discover?! After a few weeks of diplomatic prodding, I learned that, preserved in Retta’s son’s attic were close to 150 original drawings from projects ranging from Bambi to Wind in the Willows. Many were done for projects that were later abandoned like On The Trail and Toinette’s Philip, projects that bridged huge gaps in our knowledge about Disney history. They are displayed in The Hidden Art Of Disney’s Musical Years for the very first time.

AV: What can we hope for the next volume?

DG: The next volume is my dream come true: a full volume exploring the life and career of the artists of Disney’s Character Model Department, the most exciting department at the Studio, the department that Joe spearheaded and where all the best visual artists were grouped for a short while. The book will be forty pages longer than the previous volumes in the series and will feature the art of Johnny Walbridge, Jack Miller, Campbell Grant, James Bodrero, Martin Provensen and of the obscure but amazingly talented Ecuadorian artist Eduardo Solá Franco. The art of those six artists (most of whom primarily focused on character design) is absolutely mind-blowing and for most of them it will be the first time that their art and career will be explored in detail. I am immensely proud of that volume and simply can’t wait to see it in print.

Artists credits:

Top: the shadow of director Leopold Stokowski helps give a sense of scale to the bug orchestra in this concept piece by Lloyd Harting for Fantasia.

Center: stunning piece of concept art created by the Danish artist Kay Nielsen for the “Night on Bald Mountain” sequence of Fantasia.

Bottom: a stunning and never-seen-before painting by David Hall for Peter Pan.

Our deepest thanks to Didier Ghez and April Whitney at Chronicle Books