Welcome to the Hotel Transylvania, Dracula’s lavish five-stake resort, where monsters and their families can live it up, free to be the monsters they are without humans to bother them!

Welcome to the Hotel Transylvania, Dracula’s lavish five-stake resort, where monsters and their families can live it up, free to be the monsters they are without humans to bother them!

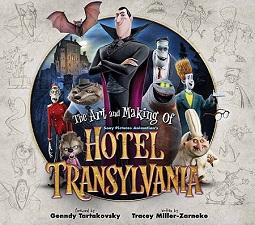

Hotel Transylvania is not only the best place for them to hide from a world that thinks they’re, well, monsters, but it’s also Sony Pictures Animation’s latest creation, directed by Star Wars: Clone Wars’ Genndy Tartakovsky.

As such, it’s a pleasure to retrieve Mark Mothersbaugh at the helm of the score, after the spectacular music he composed for SPA’s Cloudy with a Chance of Meatball.

Mark Mothersbaugh is one of this era’s most unique and prolific composers. Deeply aware of the ability of precise, multi-faceted artistic expression to deliver vital social commentary, he has perpetually challenged and redefined musical and visual boundaries.

Mothersbaugh co-founded influential rock group DEVO, and then parlayed his avant-garde musical background into a leading role in the world of scoring for filmed and animated entertainment, interactive media and commercials.

As an award winning composer, his credits include Moonrise Kingdom, 21 Jump Street, Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs, Enlightened, Rushmore, The Royal Tenenbaums, The Life Aquatic, Pee Wee’s Playhouse, and the hugely successful Rugrats television, stage and film franchise.

Mothersbaugh received the BMI Richard Kirk Award for Outstanding Career Achievement at the organization’s 2004 Film/TV Awards. He can currently be seen as the art teacher on the hit television series, Yo Gabba Gabba!

Animated Views: How did you come to score Hotel T?

Mark Mothersbaugh: I’ve been involved with animation and kids programming for a long time. I started with Pee-Wee’s Playhouse and did a lot of television. Then I did the feature film of The Rugrats. I had just done a film with Sony called Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs when they were started working on Hotel T. That’s when they asked me to get involved with it. I have two kids, who are now 8 and 11. They were younger then and when I talked to them about Hotel Transylvania, they told me I got to do it!

AV: What did you like about the project?

MM: I’ve done this job for long enough and I was looking for a relationship with people I admire. I knew Genndy Tartakovsky, the director, through his past experiences in animation and I really liked his TV things. Sometimes, you know, in filmmaking, for whatever reasons, there are dramas or unnecessary things you have to deal with that have nothing to do with making a movie. This was not one of those. It was a very straightforward production. He was very easy to work with. Really a good guy!

Also, when you see the film, you see that there’s really great characters. You know I’m an enthusiast and a participant in independent films like Wes Anderson’s. I do a lot of things in those categories, but I also love this kind of movies where the characters can live on beyond just the film. And Hotel Transylvania is such an interesting take on monsters compared to all the preconceptions that people have about who Dracula is and who Frankenstein is and who the Mummy is… They’re very likeable and actually quite shy. So, all have fully developed personalities and it was kind of very enjoyable to create themes and work on the project.

AV: At what stage of the project did you come aboard?

MM: Well, the show had different incarnations, and I was there when they were still writing it. As far as music, I started writing it about eight months ago.

AV: Director Genndy Tartakovsky wanted his animation to be “super expressive”. And so is your music.

MM: That’s what makes animation so satisfying to people that are involved in it. I mean, there’s a lot more work than your average film, either comedy or adventure. Even adventure films that are loaded with music. None of them are as complex. The music carries such an important weight in animation.

Take a field of flowers or a field of green things growing. There’s the sky above it. In film, it’s all living. As your camera moves across the shot, all things are living and breathing and moving. In animation, they can have the best computers crunching numbers, but there are things that cannot be duplicated to match real life. You can have monsters do incredible things that could never happen in the real world, that you could never do with a film camera. But the living and breathing material that’s on film, that becomes the job of the composer a lot of times to make those images come alive, to make you feel like the clouds are really moving, that they’re rolling in the sky and that every blade of grass is alive.

That’s the reason why, I think, so many animation films still rely on a large orchestra. It’s because having hundred people in a room playing music, even if it goes down to just the woodwind section – I mean maybe sixteen people playing woodwinds with their heart – brings a lot to the picture. Even directors who have directed numerous animation films always seem so happy and pleased when they get to hear their music. They really feel like the pictures finally come alive. That’s what I like about animation. It’s a lot more work because, you may create themes ahead of time, but you’re constantly working on the music the whole time that you’re writing, for all the cues.

Because you don’t see the whole picture finished. You start on animation sketches. You start writing a piece of music of Dracula walking down an underground catacomb and three months later, they send you the final animation and you see a little spider on the floor that you didn’t see before, and you have to add like a little violin line to match the spider. I guess it’s probably like if you were a painter, it’d more like painting in oil paint as opposed to painting in acrylic where acrylic dries really fast. Oil is what animation scoring is like: you’re constantly adding little things.

AV: Dealing with archetypal monsters makes the movie highly referential. How did you deal with that aspect in your music?

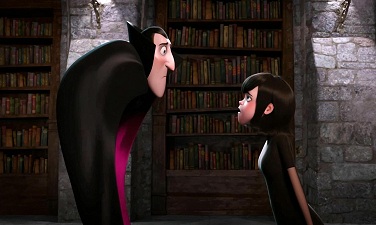

MM: There’s a few moments early in the film where I was inspired by old Frankenstein movies from the 30’s for a musical style. But I didn’t stay there because this is a world that many people aren’t aware of. A lot of kids don’t know that all of these monsters are friends. You think of them usually as lost individuals, creatures that work in solo. But all in all, they’re all pretty “good” monsters! They have kids, they have things that they’re neurotic about or worried about. Dracula in particular. His daughter just turns 118 and it’s her coming out party. He spent 118 years trying to do everything he can to squash any interest she has in the real world, and in typical teenage, she has to go exactly for what Dad is most fearing her go for. As a father, I relate to that!

AV: You’re well-known for your appealing to unusual instruments in your scores, be they electronic or ethnic. Was it the case here?

MM: Well, when all was set and done, what really felt the best was very traditional instruments. Although I used some interesting orchestral techniques, they were for the most part generally coming from traditional intruments. There was basically a 100-piece orchestra in London, in Abbey Road – I like that studio and the players there; I did four or five films with them. That said, there’s a couple of cues in this movie that are played by a zombie mariachi band…

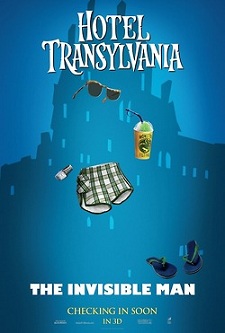

AV: How did you approach Griffin, who is actually invisible?

MM: He has one giveaway, his glasses. So, his glasses never quite disappear. For him, I used a little bit of a theremine-like instrument and some pedal-steel guitar that has an etherial feel to it. Not hawaiian or country-western, but in a way to give you the feeling of weighlessness and floating.

AV: What was the most challenging scene for you to score?

MM: There’s one that was rewritten the most times. That was early on in the film when all the monsters are arriving to the lobby of Hotel Transylvania. When we started, we were like: “maybe we should do it a little more chaotic”. So it got rewritten and then we were like: “maybe there should be a little more Carl Stalling style”. So that scene got rewritten a number of times and I think it ended up being a good way to introduce all the characters to the movie by the time we were finished.

AV: From Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs to Hotel Transylvania, you seem to feel more and more comfortable with Sony Pictures Animation.

MM: I’ve done movies through the years there. I just like the music department, that is very supportive, and the animation department very much. I also did some non-animation films like 21 Jump Street, but I met those directors, Phil Lord and Chris Miller, while we were working on Cloudy. We had such a good experience we decided to continue it with that movie. I should also score Cloudy 2: Revenge of the Leftovers. I think there’s a lot of things there that contribute to feeling secure there. I just feel that I fit in over there pretty well.

AV: It’s such good news to have you back on Cloudy 2!

MM: I’m so glad, too. If I were an animator, I think I’d wanna work on all those films because they’re fantastic in a way that’s really fun!

Our thanks to Mark Mothersbaugh, Olivier Mouroux and Kyle Rapone at SPA!